Investigating U.S. History

Lehman College and the Graduate Center, CUNY

From 1781, the thirteen United States had been bound together by the Articles of Confederation. Under the Confederation, the Continental Congress had successfully waged war, made alliances, secured loans, negotiated peace with Great Britain, and passed the Northwest Ordinance. Yet in the wake of the Revolution, the new United States faced many serious problems. Since Congress could only request funds from the States, and not levy taxes, it was unable to pay war-related debts. Without the power to regulate trade, it could not negotiate commercial treaties. Britain refused to remove its troops from forts in the Northwest territories, and Spain denied Americans access to the port of New Orleans. There was little that the diplomatically and militarily weak Confederation was able to do. In Massachusetts, indebted farmers had risen in revolt against the state's taxation policies – a rebellion that some feared would be imitated elsewhere. Both within and without the Congress, calls were made for increasing its authority. In February 1787, Congress supported a resolution for revising the Articles of Confederation; in May, representatives from twelve states convened in Philadelphia. Rhode Island took no part in the process.

The fifty-five delegates who met in the Old State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia did more than revise the Articles: they drafted a new document as a replacement. From May 14th through September 17th, they considered plans and proposals for creating a stronger, more centralized system of government. To avoid public pressure and potential protests, they deliberated in secret. Nevertheless, a number of delegates, in particular James Madison of Virginia, did take notes of the proceedings. These documents provide scholars and students with information about the actions and the intentions of the participants.

First, please choose one of the following dates and read the linked section from James Madison's Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787: May 31st; June 1st; June 11th; June 26th; July 9th; August 22nd; September 6th; September 17th.

Second, please post to the course's Blackboard site one or two paragraphs that describe what issues were being discussed on that day, what opinions were expressed, and what actions (if any) were taken.

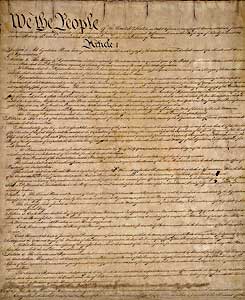

Third, please read the text of the entire Constitution.

On September 17th, the Convention signed the Constitution and forwarded it to Congress; on September 28th, Congress sent the document on to the states, which were to organize ratification conventions. From the autumn of 1787 through the summer of 1788, sustained debates were carried on in the press – through newspapers, broadsides and pamphlets–and in person in such venues as town meetings, coffee houses and taverns. Both the advocates of the Constitution, known as “Federalists,” and its critics, called “Anti-Federalists” tried to persuade voters to support or reject it. The debates in New York City's press between the Anti-Federalist “Brutus” – Robert Yates – and the Federalist “Publius” – Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison – were particularly intense, and would influence public opinion across the new nation.

First, please choose and read one of the following pairs of exchanges between Brutus and Publius which were published in the pages of the New York Journal, the Daily Packet and the Independent Journal: the Letters of

Second, please post to the course's Blackboard site two to three paragraphs that describe what issues were being debated, what main points Brutus and Publius were making, and what evidence and examples they used in making them.

Not all debates about the merits and the limits of the proposed Constitution were as formal as the journalistic exchanges between Brutus and Publius. Americans also made use of more accessible media such as broadsides and cartoons.

First, please examine this enlarged version of the cartoon “The Looking Glass” (and click on image for larger version) As you do so, please pay close attention to the words uttered by the characters, and the actions that are depicted.

Second, please post to the course's Blackboard site one paragraph in which you describe what you've seen, and in which you try to determine if the cartoon was more favorable to the Federalist or the Anti-Federalist cause.

Before becoming law, the Constitution needed to be ratified by nine states. Delaware was the first to approve it in December 1787. In the other states – with the exception of Rhode Island – special conventions were held into the following summer. Arguments by Anti-Federalists convinced delegates in a number of conventions, Massachusetts for example, to support the Constitution and to suggest a series of amendments to remedy its defects. In June 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify, and the Constitution came into effect. But until the pivotal states of Virginia and New York supported the plan, the outcome of the process was in doubt. Virginia's convention voted in favor of the Constitution in June; New York followed in July. North Carolina, where reservations about the Constitution prevailed, did not assent until November 1789. Rhode Island agreed to the new federal framework in May 1790.

First, please read the selections from the proceedings of one of the following ratification conventions: Massachusetts, Virginia and New York.

Second, please compose a broadside of 500 to 600 words in which you argue why the Constitution should be rejected, ratified as is, or accepted with amendments. Your arguments should be based on the materials from the ratification conventions and from the Brutus and Publius essays that you've read. If you need additional information, please consult the resources listed below.

The purpose of this module is to provide students with access to on-line collections of primary documents, and to encourage them to investigate and synthesize information from these sources. It is designed to be used as part of an introductory course in American History – usually the first half of the U.S. survey – or in an upper-level course that would cover the years and topics under consideration.

The activities, in particular the postings to a course Blackboard site, were designed with the limitations of Lehman's IT classroom space in mind. For other campuses, these activities could be done within a computer lab, where it might be more effective to have students work collaboratively, and to share their results with other class members.

Activity One: the links are to the Yale Avalon website for the selections from Madison's Notes. these documents are also available (but with advertising) at: http://www.constitution.org/dfc/dfc_0000.htm (.) This site, maintained by the Constitution Society, includes a calendar with links to the Notes for every day of the drafting process. The eight dates chosen are ones in which specific aspects and issues were discussed: May 31st (election of the legislature; the limits of democracy); June 1st (the national executive); June 11th (the 3/5 calculus for persons and property); June 26th (the senate); July 9th (ratio for representatives in House; counting slaves for this purpose); August 22nd (legislation regarding the slave trade); September 6th (election of the president); September 17th (Benjamin Franklin's closing remarks; signing the Constitution). So that students can discover and briefly discuss what was under consideration on the respective dates, this information has not been provided to them.

Activity Two: the essays by “Brutus” and “Publius” are also both on Avalon site and the Constitution Society's sites: http://www.constitution.org/afp.htm, http://www.constitution.org/afp/brutus00.htm, http://www.constitution.org/fed/federa00.htm

The Constitution Society sites also include a useful comparison of Anti-Federalist and Federalist essays, and a calendar linking them to the ratification process: http://www.constitution.org/afp/afpchron.htm (.)

The paired Brutus and Publius pieces in this activity are concerned with the following topics: Brutus No. 1, Publius No. 14 (the size of republics); Brutus No. 2, Publius No. 84 (the need for a Bill of Rights); Brutus Nos. 3 and 4, Publius Nos. 55, 56 (the ratio for the house of representatives; the 3/5 calculus); Brutus No. 7, Publius No. 23 (taxation); Brutus No. 8, Publius No. 8 (standing armies); Brutus No. 16, Publius No. 62 (the senate). These pairings do not include Federalist No. 10 or No. 51, since the centrality of these particular essays is an artifact of twentieth-century scholarship, not eighteenth-century politics.

Should class members need more background for the drafting of and debates over the Constitution, they should be directed to Digital History's sections on "Drafting the Constitution," "Compromises," "Completing the Final Draft," and "The Bill of Rights." There they will find a clear explanation of the processes and politics involved.

Activity Four: the edited selections from Jonathan Elliot's Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (1836) are from the Constitution Society's sites: http://www.constitution.org/elliot.htm (.) In choosing speakers to excerpt from, clear presentations and characteristic arguments were of most importance. Other module developers in the USHI made the suggestion that students should synthesize what they've read by composing a broadside.

A hyperlink to the Library of Congress's broadside collection, and a short discussion of “What is a Broadside,” is included here and in Activity Three. Digital History's “The U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights” (above) will provide students with clear summations of what was debated at the state ratification conventions.