Investigating U.S. History

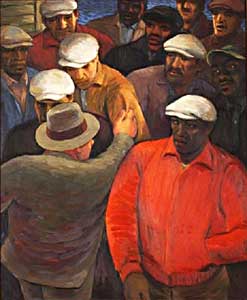

James Grosso, The Shape Up

Baruch College, CUNY

Although union activity usually grinds to a halt during periods of mass unemployment, picket lines were as common as bread lines in 1934. A million and a half workers took part in some two thousand strikes that year. They were emboldened by Section 7(a) of the National Industrial Recovery Act, which guaranteed workers the right to form unions and bargain collectively over wages, hours, and conditions. The Act was part of President Franklin Roosevelt's liberal New Deal policies, but many employers saw it as a step toward Communism and brazenly resisted it. They waged murderous campaigns against farm workers in California, autoworkers in Toledo, truck drivers in Minneapolis, and textile workers throughout the country.

This was the backdrop of a monumental showdown between ship owners and longshoremen on the West Coast. On May 9, 1934, 32,000 dockworkers in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, and other ports refused to load and unload ships under hiring and job conditions they deemed intolerable. They objected to the dreaded "shape up," where kickbacks and favoritism determined who got work; to "speed ups" that made accidents and injuries common occurrences; to brutal shifts that lasted twelve, twenty-four, and even thirty-six hours for no extra pay; and to the phony company union that permitted these abuses.

Shippers tried to bring in non-union workers, but the strikers fought back. For two and a half months they battled bosses, "goons", police, red-baiters, and the National Guard, sparking an extraordinary four-day general, or sympathy, strike of all workers in San Francisco. Was the Revolution at hand? Was Roosevelt to blame? Where would this labor upsurge lead?

This module invites an intensive study of the 1934 Pacific Coast waterfront strike and the documentary record it produced as a way to explore the broader social, political, economic, and cultural tensions of the New Deal era. It has five objectives:

The strike, like the Depression era itself, is fast receding from living memory as members of that generation pass on. Soon our understanding of those times will be based solely on the surviving documentary record. This module brings together five kinds of sources: written accounts, oral histories, photographs, artwork, and music. Each type of source provides a unique but partial window into the past. Together they can provide a deeper understanding of not just the strike but of the decade as a whole.

Any American history textbook covering the Great Depression can provide sufficient background knowledge of the period to teach or use this module. However, below are four secondary sources - three articles and one radio documentary - that try to put the strike in a broader context, assess its legacy, highlight the role of African Americans, and profile its most charismatic figure, union leader Harry Bridges. For those who want more, a comprehensive list of books and videos on the strike and the union can be found in the instructor's annotation.

Read historian Irving Bernstein's essay, “Americans in Depression and War.”

"Unemployment was the overriding fact of life when Franklin D. Roosevelt became President of the United States on March 4, 1933..."

Read journalist Dick Meister's 70th anniversary retrospective on "The Big Strike"

"The Bottom Line Few, if any, strikes have had greater historical impact than the 1934 strike of West Coast longshoremen"

"The West Coast Longshore strike had a profound impact on Black workers"

Listen to Ian Ruskin's radio documentary, "From Wharf Rats to Lords of the Docks: The Life and Times of Harry Bridges." (Part 1 & Part 2, 28 minutes each)

The following three activities may be undertaken in sequence or independently of each other, and either in class or on line.

The strike has dragged on for almost two months, paralyzing shipping on the West Coast. The governor of California is considering calling in the National Guard to break the strike and open the port in San Francisco. He has asked for representatives of five groups to meet with him to discuss the issue.

Split up into the following groups:

Read at least three of the primary documents in A. The Written Record, and note any pertinent facts or arguments that could prove useful to presenting your case at the meeting.

Your professor should set up discussion boards for each of the five groups to caucus. Discuss the issues at stake and the pros and cons of calling in the National Guard until you come to a collective decision about how to advise the mayor.

Your professor should set up one more discussion board labeled "Community Meeting." State your positions, in character, on the discussion board, and respond to the advice and arguments offered by others at the meeting. Your professor can play the part of the governor, pressing participants for clarification or elaboration if necessary, and moderating the debate. As mentioned, this meeting can also take place in class.

Divide yourselves into five groups, each of which will focus on one of five kinds of historical sources:

Skim the sources in their respective record groups and select one or more sources for closer analysis. Write five paragraphs analyzing your chosen documents using the questions suggested in each of these sections.

Your professor should set up discussion boards for each of the five record groups. You should post your papers on the appropriate board and respond to the posts of at least two others in your group or in other groups. You may also opt to share and discuss your documents in class.

Members of the five groups should work together to create multimedia essays and presentations using at least three of the five different kinds of sources in this module. Below are five suggested topics. This final activity can function as a term paper or project. Presentations may be scheduled for one day or spread out over time.

This module is designed to be adaptable for use in U.S. history survey courses as well as in more specialized courses in labor studies, California history, or the 1930s. I have used all three activities in a survey course in which I devote just two week (four class meetings) to the Great Depression. I usually devote the first meeting to lecturing on the stock market crash, President Hoover's response, the agricultural crisis, and FDR's election and first hundred days in office. I focus on other themes (WPA, “Lunatic Fringe,” African Americans, the labor movement, etc.) in the second meeting and end by introducing The Big Strike website. Students complete Activity 1, the Community Debate, outside of class for homework (although the community meeting works well in class too).

Activity 2, the document analysis, is probably the most flexible and useful of the activities. It's quite all right to have the students focus on just one set of records, say the oral histories or the photographs. I like them to present their “reading” of the texts or images in class because the students will often challenge each other's interpretations and inferences, and the lessons learned here will carry over to their engagement with primary sources they encounter in other contexts or courses.

It is one thing to analyze a single source, but quite another to use it in conjunction with others to construct a narrative structured around an original argument. Activity 3 is recommended as a term paper option. Here I devote the last day of class to presentations. It is gratifying to see them weaving together government documents, visual images, and oral history quotations to make their arguments. Some students bring in guitars, keyboards, and CDs to sing, play and discuss traditional or original labor songs. Their engagement with the culture, politics, and social movements of the 1930s is palpable and the semester always ends on a good note.

I would like to thank David Jaffee, Bill Friedheim, Pennee Bender, and Michael Whelen for their guidance, Angelo Angelis and Rebecca Hill for their teamwork, Janet Heettner for her web work, Joshua Freeman for his critique, and Harvey Schwartz for his expertise and solidarity.